By Gary Butler

Which family-run collision repair shop in Cocke County, Tenn, has weathered the trials and tribulations of keeping a business fraught with obstacles and constantly shifting challenges alive and well for almost four decades? Strange that you should ask.

Strange’s Custom Auto, that is, located at 430 Industrial Road in Newport.

When the Automotive Report first interviewed owner Tim Strange in 1998, he had already developed a robust customer base and a sterling reputation as a high-quality repair facility, but he didn’t foresee at that time just how daunting it can be to “keep the wolf away from the door” for a collision repair shop—or any business for that matter—in an economically-distressed community.

“We had a very healthy customer base for several years and people raved about the quality of our work,” Strange said, “but things in the area took a turn for the worse when several of the local manufacturing plants closed down or relocated.”

Because his shop is located centrally in the middle of what used to be a moderately dense industrial park, for a rural community like Cocke County, he said at least half of his customers worked at one of these plants. So when several of the plants closed down, one-by-one, many of those customers either moved to a new location looked for new employment opportunities in neighboring communities when their plant simply closed its doors for good.

“Add to that the number of older customers who stuck with us for years who have gradually passed away, and it’s easy to see why we got discouraged for a while,” he said. “As a matter of fact, we end up sending flowers to the families of these older customers about once a month now. I was 23 when I started this business in 1982, and most of my customers then were in their 40s. A lot of those people aren’t around anymore.

“We have held on as best we could, but between losing a big percentage of our customers to things out of our control, and the struggle to stay current with technology that changes almost daily, it has not been easy,” Strange said.

And if those factors were not enough to lose sleep over, Strange said the rigors of trying to wade through insurance company guidelines and requirements necessary to maintain his shop’s status as a Direct Repair Program (DRP) facility have sometimes “sucked the joy” out of doing a job that is supposed to be more customer-oriented than insurance company-oriented.

“The DRP program was probably a good thing at one time, but it has evolved to something that confuses customers far more than it puts them at ease,” he said. “And satisfying the customer is supposed to be what any business is about, repair shop, insurance company, or whatever.”

Strange adds his voice to a growing chorus of collision repair owners and managers who find themselves “caught between a rock and a hard place.”

“The insurance companies have pushed the DRP program for a long time now, but customers and shop owners are getting the short end of the stick more and more,” he said. “From our perspective, we can’t charge mark-up on a tow bill, or storage for cars sitting here, and you don’t get paid to do total-loss sheets.

“I might have to pay my estimator for three hours to do the work the insurance adjuster used to do, so I’m paying for someone to do the insurance company’s administrative work,” Strange lamented. “When places like ours started with the DRP programs, they [insurance companies] would say ‘it’s going to be a win-win for everybody, because when the customer comes to your shop and he wants you to fix his car, he has his insurance, you do the estimate, fix the car, send us the bill.’ There were basic guidelines, of course, as you would expect.

“Now, you have to run the parts through a computer system, and that system scrubs it and tells you where to get your parts at,” said Strange. “You can’t charge mark-up, have to do this and that, do courtesy estimates, and if a customer just wants you to sign his estimate because he’s cashing out, we end up doing the adjuster’s job for free. It’s a different business than it was a few years ago.”

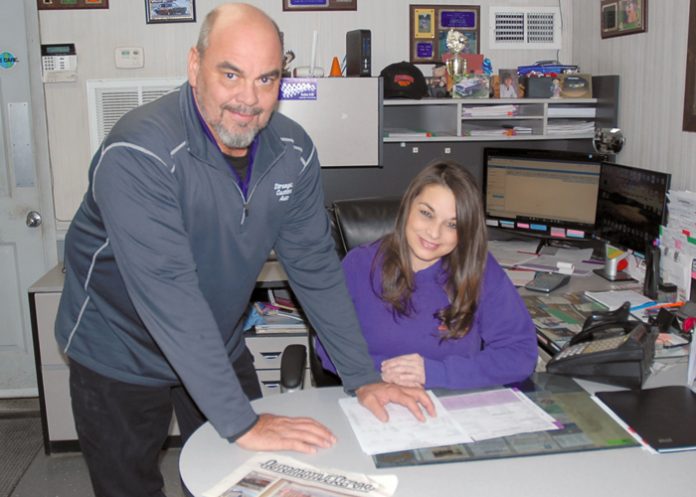

Not all of Strange’s reservations about the DRP program revolve around money, he said. He and his sister, Janet, who has worked by his side for many years as his administrative assistant, say they feel bad for customers who are “intimidated by insurance companies that make them believe they have to get their vehicles repaired at a DRP shop.

“What they don’t tell them is that we, the repair shops, are the ones who are guaranteeing the work—not the insurance companies,” Strange said. “But people are often afraid their policy will be canceled or their rates will go up if they don’t follow the insurance company’s ‘suggestion,’ and that just isn’t true.”

“I’ve seen both sides of this issue,” said Janet, “because I worked for years at a local insurance company. And the customer has the absolute right to take his or her vehicle to any shop they choose.”

Both Tim and Janet Strange say they believe no more than about 15 percent of customers are aggressive enough to demand what they want, and this factor just emboldens the insurance companies all the more.

Strange also echoed other shop owners who have said it would likely take roughly a million dollars to buy into or start up a collision repair business today.

“First off, you’d need a good downdraft paint booth, about $90,000, a frame machine and measuring system, another $60,000, and a mixing room would be about $20,000,” he said, “and those are just the basics. Add to that another $15,000 for a fire-suppression system in the paint booth.”

Strange noted that codes and ordinances for things like the fire-suppression and other safety and ecology issues are “even more stringent in other counties, many of which are less economically distressed than ours.

“Hamblen County, right next door, for example, requires you to get them to approve the piece of land you’re going to put your building on, and that’s just the very first step,” he said. “Over here, we were able to build a 30 by 40 addition to our paint building in 2012, bringing our total square footage to about 7,000, without jumping through that particular hoop.”

Another challenging aspect of doing collision repair work in today’s world, according to Strange, is the difficulty in finding solid, dependable body and paint technicians.

“Techs are just about impossible to come by, especially good ones,” he said. “When we lose one, he will typically float around to other area shops and, as often as not, end up back here. We have a guy here now who’s been with us three or four separate times — I’ve lost count.”

As to why techs come and go, why they don’t settle into a long-term relationship with any one shop, Strange speculated that there are multiple possibilities.

“Some get dissatisfied with the work somewhere, or maybe the pay, maybe they strike out and try to make it on their own for a little while, then eventually show up back here,” he said. “It’s like a revolving door.”

When asked about the current crop of vo-tech students, Strange isn’t much more optimistic.

“One of my guys who’s worked here several times and started as a teenager is the vocational teacher at the local high school,” he said. “And not only do I know him very well, but I’m also on the advisory committee at the school. So he says, ‘If I see someone in the program who I think would work out well for you, I’ll send him your way.’

“He’s been here three years and has yet to send me anyone,” Strange said.

Strange said he thinks the biggest problem with students graduating from vo-tech school, and young people in general these days, is a lack of a good work ethic.

“They seem more interested in sitting at a desk with their phone or computer than getting their hands dirty,” he said.

Strange also said the high expense of vehicles themselves and the high cost of repairing them is also taking a toll on shop owners. And part of the cost associated with collision repair is what it costs to “jump through the diagnostic hoops you have to deal with, and the down-time some of that brings with it.

“Now you have to take classes on computerization, and on how to run a scan tool. And we have to do a pre-scan on a vehicle when it comes in to see how many codes there are on it, and how many are accident-related,” he said. “Then do another scan before the car leaves to clear codes that were due to the accident.”

Another expense that Strange suggests may not be cost-effective these days is the cost of keeping his techs and himself I-CAR- and ASE-certified.

“To me, those certifications are more of a piece of paper than they are an asset,” he confided. “The DRP programs require you to have it, but that’s about it.

“I can name one [insurance] adjuster who paid for and attended an I-CAR training session because he wanted to know more about what it takes to repair a vehicle, and when he came back even he said it was a waste of money,” Strange said.

When Strange was asked about how or whether driverless cars are likely to affect his business, he just laughed.

“They may end up in Knoxville, or other urban areas, but around here they don’t even have yellow or white lines on half the roads,” he said. “And never mind that many of the roads in this county are gravel. It’s hard to see how a driverless car is going to work here, at least anytime soon.”

Things aren’t all gloom and doom for the Stranges and their business, however. Tim Strange said, jokingly, that he can always fall back on his work as a painter of fire hydrants, well pumps, and tricycles, all of which he has painted at one time or another in his 36 years in the business.

“And helicopters,” he added. “I painted a Bell two-seater training helicopter one time, and the guy brought it in here one piece at a time. My deal with the guy was that I would paint it in exchange for flying lessons, but it turned out one lesson was enough for me.

“While we were in the air, I asked him ‘what happens if the engine shuts down,’ and he said ‘You die.’ No more lessons for me after that, and that was the end of the barter system,” he said, laughing about it but clearly grateful to be alive.

Strange may not be flying high, at least in a rotor-propelled craft, these days, but he said he still takes great pride in turning out a quality repair and serving his customers to the very best of his ability.

“We may feel hamstrung sometimes by rising costs, the never-ending quest to find dependable techs, and the downward spiral of difficulties involved with jumping through these DRP hoops, but we will never turn out anything other than the highest quality repair,” he said. “Anything less would mean it is time for us to close our doors and go home.

“And we aren’t going home, not anytime soon,” he said. •