By Steve McLinden

Cruise up New Orleans’ magnificent Magazine Street from the French Quarter and into the city’s historic Upper Garden District and you’ll see rows of stately pre-Civil War homes, chic shops, trendy eateries, quaint coffee houses and, eventually, two radiant rainbow-colored signs that read, “A. Vargas Body Shop.”

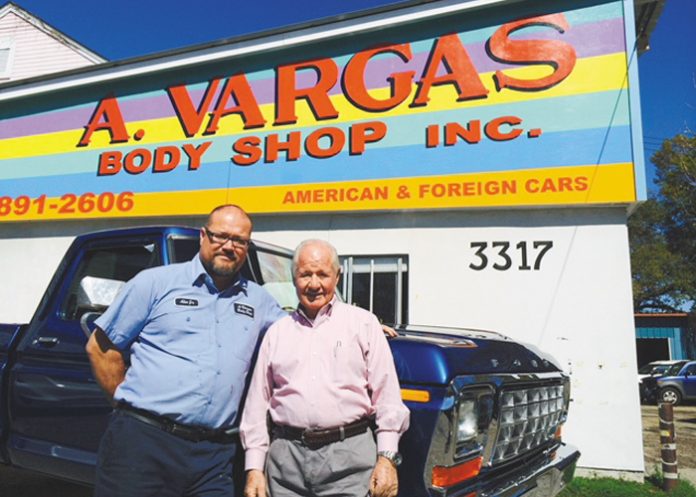

The subject of the signs, hand-painted years ago by a local artist, is a 48-year-old collision-repair shop created by one Alejandro (Alex) Vargas, who grew up on a cattle ranch in Peru before immigrating to the U.S. at age 28. Despite having virtually no auto-repair experience, Vargas managed to latch onto a job at a small auto body shop soon after he arrived under a manager who was patient enough to teach him the ropes.

“I knew I had better learn fast, so I did,” Vargas recalled.

Vargas opened A. Vargas in 1972 at a smaller location and in 1979 moved it to its present locale at 3317 Magazine near Louisiana Avenue, which has since become a Garden District institution. Though the section of Magazine Street that’s home to A. Vargas is zoned for retail, restaurants and light-service businesses, the shop is “grandfathered in”” because the area was zoned for industrial use when it first opened.

On this warm, humid spring morning, the founder’s son, Alex Vargas Jr., was walking a customer through what was going to be expensive repair job on his SUV that would involve realignment of all four doors, all new molding, new back bumper and numerous others needs. The customer didn’t flinch at the estimated repair cost of $5,000, most of which would be covered by insurance. It doesn’t hurt that the two Vargas men project an air of empathy and light-heartedness that serves to calm rattled customers. In fact, numerous shop patrons and neighbors tend to stop by for an energizing chat with the elder Vargas, time permitting, said his son.

Customers come from all over the region, including the entirety of New Orleans, as well as Metairie, Kenner, Laplace, Gretna and other surrounding towns. A. Vargas also seems to be the body shop of choice for college students at the city’s many colleges, including Tulane, Xavier, Loyola and the University of New Orleans, said the owner. The shop does little advertising other than a small Yellow Page listing and relies heavily on return trade.

“We are now seeing the third generation of customers from the same family,” said Alex Jr.

The informal shop motto of “make all our jobs look like they just rolled off the factory line,” hasn’t hurt the shop’s return-customer trend, he said.

Atop the shop’s main garage, a tree trimmer walks gingerly along the metal roof as he carefully crops a 175-year-old tree looming high above the property. The city has restrictive laws about historic trees in the Garden District, so the Vargases know they must tread cautiously and hired a seasoned trimmer.

Compared to other New Orleans body shops, A. Vargas got off relatively easy during Hurricane Katrina in 2005. It sat just high enough to avoid major flooding but still incurred wind damage after a limb from the giant tree broke through the shop roof, destroying the paint booth and creating an entry point for looters to make off with thousands of dollars in tools. But because other area shops couldn’t reopen for months — or in many cases, at all —the work flow picked up and the shop got busier than ever, well into 2006.

The Vargases had waited out the storm in Jackson, Miss., and upon returning, discovered the shop founder’s house had taken on nearly three feet of water. Son Alex, who lived in LaPlace 20 miles or so west of the city, suddenly had a packed house full of relatives as home repairs were made. There were other silver linings surrounding the calamity, said Alex Sr. In the end, the deadly storm “helped created a lot of jobs for a lot of people,” he said. “And it also chased some of the riff-raff out of town.”

The shop’s deep, gated lot contains room for more than 25 vehicles, making it an anomaly for this parking-starved section of New Orleans, where other businesses rely on a limited number of street meters. Staffers know many of their Garden District patrons by name and offer them friendly conversation and rides home once they’ve drop off their cars.

The shop has seen more than its share of quirky shops take up residence nearby over the years. The proprietor of a now-closed voodoo shop across Magazine Street would, for no apparent reason, regularly leave dolls, potions, powders and other voodoo and witchcraft “gris gris” on the sidewalk just outside A. Vargas.

“Dad would just pick them up and put them in front of the guy’s shop,” said Alex Jr. “He doesn’t believe in that stuff. Afterward, you’d see the guy out there scrubbing down the sidewalk with bleach and muttering to himself. We both got a big laugh out of that.”

Based on the overwhelming positive vibes conveyed about A. Vargas on social media, it’s obvious that no hex has been put on the place. One long-time customer on Google wrote: “It’s rare to visit a business today with no turnover of people who work there; we wish we didn’t need them so frequently, but when we do there’s nowhere else we’d go with our cars.” The shop is “great about communicating with the customer,” noted another. “Alex works with the insurance company and always advocates for his clients; the work they do is unparalleled and my car looks brand new whenever I leave the shop.”

In a previous profile written for a New Orleans business publication, a local trial lawyer and loyal shop customer, Roger Stetter, described founder Vargas as “a quintessential self-made man who lifted himself from a low-paid worker to a successful entrepreneur and a credit to our country and work ethic.”

Still spry and able-bodied, the older Vargas has no immediate plans for full-time retirement.

“I enjoy coming in every day and being active and seeing people,” he said. •